As we open our hearts to the future, we can learn from the closed adoptions of the past.

Adoption’s early days

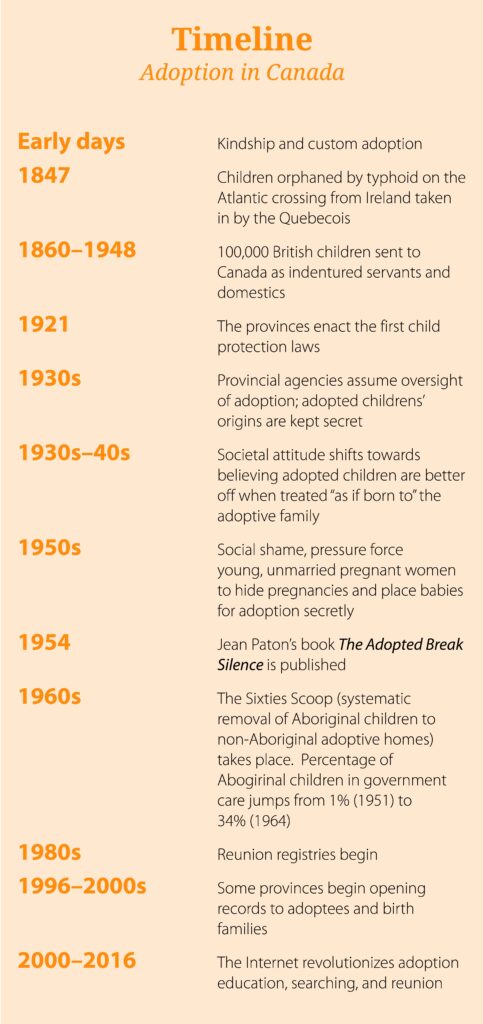

Before the 19th century, what we now think of as kinship, clan, or custom adoption—compassionate adults incorporating orphaned children into their families—was essential to many cultures. For example, when Irish immigrants died of typhoid on the Atlantic crossing of 1847, thousands of orphaned children were taken in by French Quebecois families. Parish priests even carefully recorded the children’s family, parish, and county of origin and the name of the vessel on which they’d travelled. However, the attitude that a child had rights and needed both the protection of the law and the love of a permanent family evolved more slowly.

In the late 19th century in North America, legal adoptions were rare and limited to wealthy families. Things looked quite different for the poor. Maria Rye, an Englishwoman, made a profitable business of transporting over 3600 British orphans to Canada. At least twenty-five other organizations participated in similar ventures. From 1860 to 1948, 100,000 British children were distributed across Canada as indentured servants and domestics. Only two percent were orphans; the rest were taken from families too poor or sick to care for them. Although these children’s backgrounds weren’t secret, they also usually weren’t considered important enough to document. The children’s memories were their only tie to their past and their history.

Secrets and silence

The first laws regulating adoptions were passed in the US in 1851. Canada didn’t follow suit until 1921, when it created provincial laws to oversee the welfare of its children. By the 1930s, most western countries were committed to legal and regulated placement processes for children.

During this time, adopted children were generally thought of as “lower class,” and adoptive parents as inherently superior. Psychologists, social workers, and policy makers believed it was in everyone’s best interests to keep the child’s origins a secret. Birth mothers had few rights, and social workers screened out information that would identify birth and adoptive parents to each other.

Things began to shift in the 1950s, when the number of babies being placed for adoption increased steadily. An adoptee named Jean Paton wrote a book called The Adopted Break Silence, in which she argued that adopted children should be able to know the identities of their birth parents in order to understand their connection to humanity. Most adoption agencies did not accept this, though, and secrecy remained the norm.

During this same time period, it was common for young, unmarried, pregnant women to be sent away from home to live with relatives or in religious institutions. Their babies were placed for adoption, sometimes against their mothers’ wishes. One markedly dreadful institution of this kind was the Ideal Maternity Home in Nova Scotia, run by William and Gladys Young. This was the infamous “Butterbox” institution, where healthy babies were sold to adoptive homes while babies who were sick or otherwise deemed unadoptable were left to die, and were buried in butter boxes from the local dairy.

Civil rights and the Sixties Scoop

In the 1950s, the US civil rights movement influenced Canada’s adoption policies, and transracial adoptions became more common. These families’ differing skin colours made their adoptions obvious; secrecy simply wasn’t an option, and gradually, attitudes toward closed adoption and secrecy began to change.

In the 1960s, increased access to abortion and birth control and reduced stigma against single mothers led to a decrease in the number of babies available for adoption. During this same time period, however, the Sixties Scoop began in Canada. Social agents rounded up Aboriginal children by the car or even bus load, sometimes stripping villages of the majority of their children despite the vehement protests of their families and communities. These children were placed for adoption with non-Aboriginal families, who often didn’t know the truth behind their children’s apprehensions until many years later.

The Scoop caused horrendous problems for Aboriginal communities, which—in combination with increased awareness of importance of racial identity and cultural affiliation—eventually forced changes in social policy. However, Aboriginal children continue to be vastly overrepresented in Canada’s child welfare system.

Adoptees create change

From the 1970s onwards, children who were adopted in closed and secret adoptions grew up and began to organize, advocate, and agitate for their right to know their heritage. Thanks to their voices, the desire to know one’s biological roots began to be understood as a genuine, legitimate need. It wasn’t just for the abused, the disturbed, and the unstable, nor was it inherently a threat to or negation of the adoptive family’s bond.

Gradually, institutions began to change to accommodate adoptees’ demands. Reunion registries were established in Britain, Canada, and the US, and changes in legislation gradually made it easier for adoptees to find their birth parents, and vice versa. Eventually, the concept of “need to know” evolved into an understanding of adoptees’ right to know their origins, and to the development of open adoptions as we know them today.

Openness and love in the 21st century

Today, adoption records are much more open and accessible. Adoptive parents strive to learn as much as they can about their child’s birth family, and often work together with birth families to support and nurture their child in whatever way works best for everyone.

Of course, not all adoptive parents want, or can safely allow, contact with birth families; not all birth families want contact with the adoptee. Even so, the secrecy of the past seems impossible today.

Adoptees read books such as The Primal Wound and Attachment Disorders, and realize certain struggles are common to adoptees and aren’t a result of personal failings or individual pathologies. They find and connect with like-minded people on the Internet. They form support groups and encourage discussion. They use social media and DNA technology to find their birth families.

Some struggle with the overwhelming long-term effects of early trauma; others find insight, therapy, or coping skills that allow them to successfully regulate their early emotional and physiological upheavals.

Adoptive parents, too, can easily find advice and support from others who are dealing similar challenges. Organizations such as the Adoptive Families Association of British Columbia offer cutting-edge educational options, such as webinars, which allow them to learn about the latest and most useful insights into the lifelong journey of adoption.

Love isn’t mentioned much in adoption history books—not the ones I read, at least. It’s as though an entire section on love in the adoption story went unwritten, or that adoptions in the the past were motivated solely by convenience, need, and duty. Surely, though, love existed, even if the records don’t reflect it.

Secrecy was once seen as crucial to the development and preservation of love in adoptive families. Adoptive parents today know that the more we know about our children’s birth family, the better we will be able to support and guide our kids as they grow. We understand the harm secrecy can cause, and respect and support adoptees’ right to the truth of their heritage. And, through today’s open adoptions, we live out an expanded definition of love—a definition that makes room for truth.

From Marion Crook’s book Thicker than Blood: Adoptive Parenting in the Modern World.