Is it lying? No, it’s confabulation and there’s a big difference!

Time and time again we hear from adoptive parents that one of the hardest behaviours to take is children lying to them. They experience the lie as a personal affront, a show of disrespect, and a harbinger of anti-social behaviour to come. There are many reasons why adopted children may lie, ranging from the fight or flight reflex, fear of rejection or punishment, to delayed development. It is not uncommon, nor is it usually something to be alarmed about. This article, however, is not about lying, but about confabulation – and the important difference between the two.

Confabulation is the replacement of a gap in a person’s memory with false information that he solidly and consistently believes to be true. Recent research suggests that all of us do this routinely to some extent, especially when we are pressured or influenced to discuss things that are difficult to explain (like personal choices, opinions, or preferences). However, confabulation is particularly common, often blatantly so, in children and dementia or brain-injured patients because of a lack of function in the pre-frontal lobes of the brain – in the case of children, this area of the brain is still under-developed; in the latter case, it has been compromised by the disease or injury. Either way, the memory retrieval process has been impaired leaving gaps in the person’s memory and when the person or child feels pressed to talk about something (usually by being questioned about it) the brain automatically begins to fill in the gaps in order to make the memory complete and cohesive. In these individuals, the information they give may be quite fantastical and impossible but, nonetheless, completely believable to them.

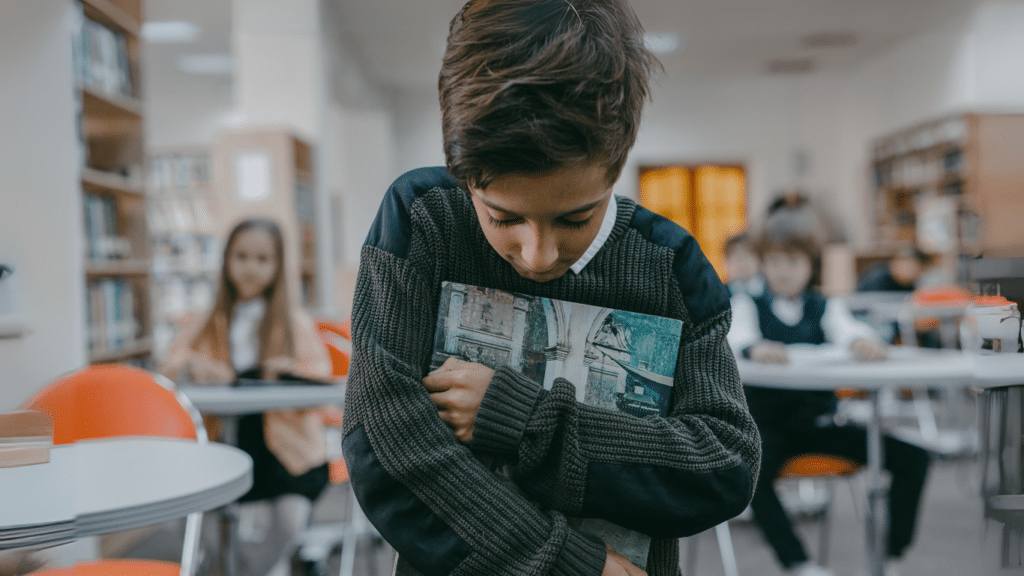

For our adopted children who have often experienced trauma and/or abuse, the brain development is often delayed and hence we see confabulation still occurring at an age when other children have learned to report more accurately. Similarly, children with special needs, such as brain injury caused by pre-natal exposure to alcohol and/or drugs, will exhibit this behaviour more often and likely for a longer period of time. There may also be an element of approval seeking or wanting/needing to present their story as more exciting and entertaining, but, for the most part, it is a cognitive inability to sort the real events from the imagined ones that leads to an inaccurate report. In confabulation there is no intent to deceive, but the story told may well lead away from the truth of the matter.

Even as we accept this as a developmental stage, we need also to recognize that it can be problematic socially for our children as they risk being labeled as dishonest. While there is no treatment for confabulation in children, there are a few strategies that may be helpful.

First and foremost, understand that the child is not deceiving you. More likely than not, he is seeking attention or approval. Do not be overly confrontative with the child and do not refer to confabulation as lying. On the other hand, it’s okay to identify the variance from the truth. One way of addressing an undesirable behaviour without shaming the child is to “externalize” the problem, meaning to set it aside from the child himself. For instance, in a friendly or amused way, “Oh, I hear the Storyteller again. I think I can tell which part of that story is yours and which part is the Storyteller’s. He’s really good at telling stories, but so are you, and I like yours most because they are real and his are imagined” (note: “real” as opposed to “true” and “imagined” as opposed to “lies”). Now the child feels valued and the real account is shown to be preferred and, therefore, reinforced.

Another way might be to acknowledge the child’s imagination and encourage them to write stories. Then you can praise them for their story-writing skills, while casually using the story to talk about which parts are real and which parts are imaginary. Your goal is always to support your child through their natural developmental path which includes moving towards more accurate reporting of events. Insistence on the truth, consequences, or punishment may coerce or even scare a child into saying what you want to hear, but this will likely only serve to shame and confuse the child whose brain continues to confirm their original story.

Janis Fry, MSW, is a former Manager, Program Services at the Belonging Network.