Openness in adoption enables members of the adoption circle to maintain family and cultural connections and relationships, and assists the child in developing a strong, healthy identity.” This is one of the five core values guiding the adoption practice for BC’s Waiting Children, and one that is contributing to the changing nature of adoption.

Led by recent legislation, Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) social workers are being much more proactive at helping children keep connections with their birth families. The Child, Family and Community Services Act (1996), includes “maintaining a child’s kinship ties” as one of its guiding principles, and the Adoption Act (1995) allows for openness agreements.

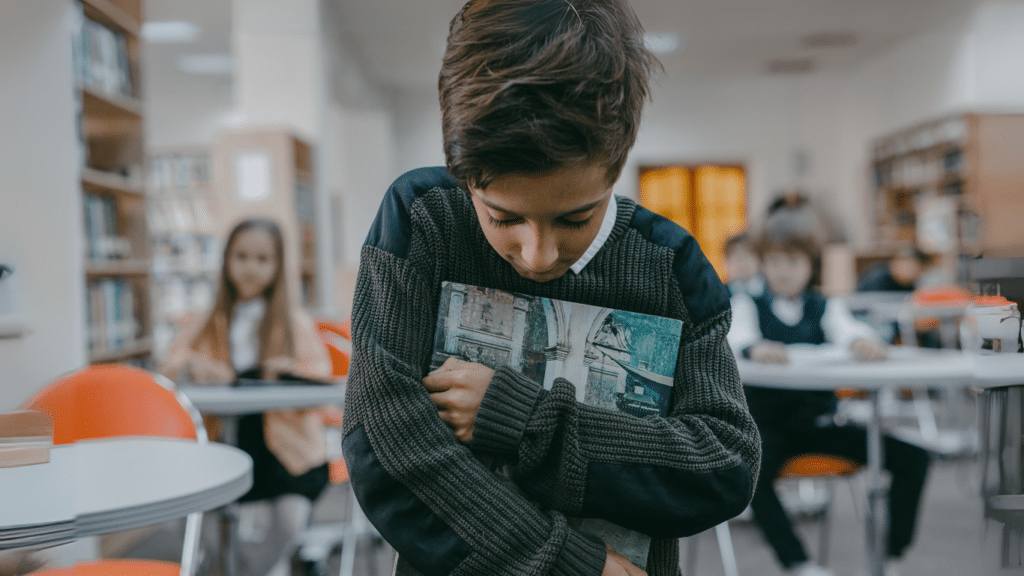

What does that mean for adoptive parents? Many believe that open adoption is beneficial for their children, but are apprehensive about managing relationships that they fear could be harmful for the child or disruptive to their family. I think the key to success lies in two strategies: putting yourself in the child’s shoes so that you can understand the strength of their need to keep connected with those they love, and developing confidence that you can deal with tricky situations.

Adoption is for children

Think about this: when you got married (let’s assume you are married), you probably did not say to your spouse “now that you’re with me you can’t see your family members any more.” So why would we tell a child that she can no longer see her birthmom, or her auntie who had visited regularly while she was in foster care?

The Kinship Center, a leading agency in the field of open adoption located in California, offers some wisdom: “Amputation does not work in matters of the heart. We must honour a child’s heart; children love forever and love deeply.” If we cut children off from those they love, whether it is birth family or foster parents, they will lose a part of their heart to the grieving they must do, and they may never get the wind back in their sails. We need to use the child’s existing attachments to help them build new attachments in their adoptive family. And keeping connections avoids the child having to do all the work of finding their kin when they are older, as they will inevitably do.

Relationships can be difficult

Might these relationships be a challenge? Absolutely, yes. Children in the child welfare system come from families with issues such as drug addiction, alcoholism, unreliability, physical or emotional abuse, inability to put the child’s needs first—all of those reasons that have caused the child to come into care. Helping your child to keep a connection with birth family could be hard work and could take a great deal of maturity on your part. Most people, though, already have experience dealing with difficult people. How many don’t have someone in their family or kinship network who drinks too much, has a mental illness, acts inappropriately around children or doesn’t do what they say they will do? You probably already have strategies in place for managing these kinds of behaviours. It’s all about knowing your boundaries and being clear that your job is to keep your children safe.

An agreement in good faith between two parties

The openness agreement is a tool you can use to set your initial boundaries. It is a starting place. As your relationship with your child’s birth relative progresses, the terms of your agreement may change. It is always easier to expand an agreement than to narrow it, so be sure you don’t agree to more than you are comfortable with at the beginning. The social worker placing the child with you should have recommendations about which connections need to be kept, and what type of contact is appropriate. Then, as you get to know each other, you may decide it is safe and beneficial for your child to have more frequent contact, or to have visits if there were none initially. Relationships change over time, and it may be appropriate to have more or less contact at various stages of the child’s development.

Here’s an example: if you had a long-lost cousin arrive from Australia, someone you knew a little bit about but did not know well, and they asked to take your kids for the weekend, what would you do? You would probably invite them over for dinner and spend some time getting to know them. It would likely be quite some time before you were ready to let your children visit unsupervised with this person, and you might not ever decide to let them stay for the weekend. The same applies to a relationship with a relative of the child’s whom you don’t know. You will want to be there for any visits until you feel satisfied that you know the person and environment well, and you may never leave the child unsupervised. This also helps the birth relative to see the child as a member of your family, and should help them understand how their relationship with the child has changed. You may want to have family visits. Many birth grandparents have become grandparents to all the children in an adoptive family.

If safety has been an issue while the child was in care, it is unlikely that direct contact (visits) will be appropriate. In that case you can support your child’s need to know about birth family by agreeing to an exchange of letters and photos, allowing you to monitor the content before deciding to show them to the child or to keep them for later.

Experienced adoption professionals say that adoptive parents with the following characteristics have what it takes for successful open adoption: confidence, risk-taking, sensitivity and knowledge.

If you are struggling with a difficult relationship and you are tempted to end it, remember to ask yourself whom the relationship is for. If you truly believe that the relationship is damaging your child, you might need to consider modifying the type of contact you have for a time. If you want out because the relationship is inconvenient or takes a lot of effort on your part, take a deep breath and remind yourself that openness is supposed to be for children. When they are grown they will make their own decisions about whom they keep in their lives.

Kathryn is an MCFD Social Worker